Saving Power in Danger: Michael Shellenberger Keynote Address to IAEA

"As-salāmu ʿalaykum." EP President Michael Shellenberger addressing IAEA quadrennial inter-ministerial in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (UAE)

October 31, 2017

by Michael Shellenberger

As-salāmu ʿalaykum.

Thank you Ann and Ayhan and everyone at the IAEA who organized this important event. I am honored and intimidated by the privilege to address such an important gathering during such an dangerous time.

1.

In 1953, the father of the atomic bomb wrote an essay for Foreign Affairs aimed at the newly elected American president. “We may be likened to two scorpions in a bottle,” Robert Oppenheimer wrote, “each capable of killing the other, but only at the risk of his own life.” He urged President Eisenhower to level with the American people about the terrifying new reality of mutually assured destruction through nuclear weapons.

Eisenhower was persuaded. But early drafts of his speech “left everybody dead on both sides with no hope anywhere,” Eisenhower fumed. “Is this all we can do for our children?” he asked. Eisenhower soon realized he needed to speak to the whole of humanity, not just Americans.

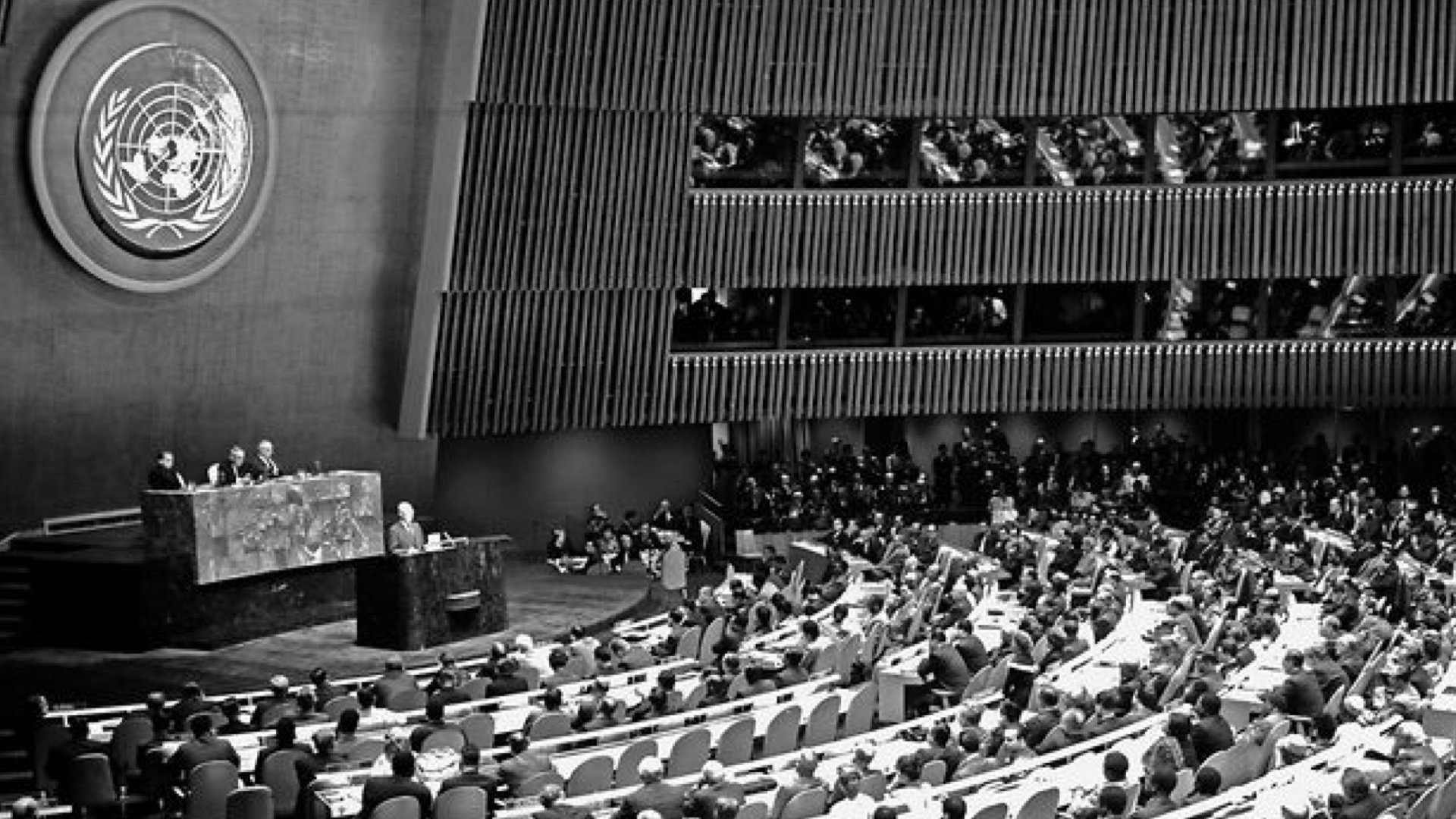

On December 8, Eisenhower walked to the podium overlooking the United Nations General Assembly. It loomed like a cathedral. But behind him hovered not a cross but a garland of olive branches, protecting Earth. He urged the parishioners to seize light from the darkness.

President Dwight Eisenhower at his "atoms for peace" speech at UN General Assembly

The horrible new technology could be harnessed to “provide abundant electrical energy in the power starved areas of the world,” he said, and illuminate a path to peace.

After Eisenhower was finished there was a pause before the parishioners rose in unison. They rewarded the former military man with a standing ovation that lasted ten full minutes. Atomic humanism was born.

In the decade that followed, most conservationists embraced his vision. “Cheap energy in unlimited quantities,” wrote the president of the Sierra Club in 1966, “is one of the chief factors allowing a large, rapidly growing population to set aside wildlands, open space and lands of high-scenic value.” He added, “Even our capacity and leisure to enjoy this luxury is linked to the existence of cheap energy.”

Nuclear power, most educated people believed, had turned out to be a blessing in disguise. It would put an end to scarcity, guarantee the peace, and protect the environment. And wasn’t that, after all, what everyone wanted?

2.

One year later the German philosopher Martin Heidegger penned a famous essay on “The Question of Technology.” In it he argued that the greatest danger we faced came from within us, not from within our machines.

We were at risk of mindlessly treating the whole of nature as a standing reserve of resources for our consumption. We were at risk, in short, of viewing something sacred as profane — of seeing nature for the way an engineer would: as a kind of machine. The use of “modern technology,” he wrote

…puts to nature the unreasonable demand that it supply energy which can be extracted and stored as such… Air is now set upon to yield nitrogen, the earth to yield ore, ore to yield uranium…to yield atomic energy…”

This fundamentally selfish way of seeing the world would be the death of us, his followers agreed. “It’d be little short of disastrous for us to discover a source of clean, cheap, abundant energy,” wrote anti-nuclear leader Amory Lovins, “because of what we would do with it.” Said Paul Ehrlich, “In fact, giving society cheap, abundant energy at this point would be the moral equivalent of giving an idiot child a machine gun..”

They quickly dethroned the atomic humanists. “Our campaign stressing the hazards of nuclear power,” wrote the new head of the Sierra Club, "will supply a rationale for increasing regulation… and add to the cost of the industry…”

They launched a crusade first in the US, then in Europe, and then around the world. They gained power from danger. “A nuclear accident could wipe out Cleveland,” Ralph Nader said, “and the survivors would envy the dead.”

The solution, they said, was to harmonize society with intermittent energy flows that didn’t produce very much power. The “wind mill does not unlock energy in order to store it,” said Heidegger, praising the ancient technology.

What of atoms for peace? It was a fig leaf, said the anti-humanists, not an olive branch, a way to trick humankind into accepting an apocalyptic and high-energy way of life.

3.

Fifty years hence we can see the mixed fruit from atoms for peace and the war on nuclear.

Fifty one nations have nuclear energy; just nine have weapons. What more proof is needed that nuclear energy prevents the spread of nuclear weapons than the fact that South Korea has nuclear energy and no weapon while North Korea was denied nuclear energy and obtained a weapon?

And yet we are on the precipice of a new arms race and appear closer to nuclear war than at any other point since 1961.

No nation has done more to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and the diversion of dangerous materials than my own. Yet our invasion of Iraq, betrayal of Libya, and refusal to disarm have all stretched the nonproliferation fabric to a tearing point.

Nuclear provides over one-tenth of the world’s power and helped lift Japanese, South Koreans, and Indians out of poverty.

And yet nuclear’s share of global power peaked in the mid-1990s at nearly double what it is today. And nuclear energy started its decline in absolute terms a half decade before Fukushima. Now, with the crisis facing nuclear accelerating, the world is a risk of losing twice as much nuclear as it adds between now and 2030.

The last 15 years has seen the extraordinary growth of intermittent renewables, particularly solar and wind. But how much electricity was generated from this investment? Not very much.

You can see from this chart created by a team of scholars including Environmental Progress Senior Science Advisor, James Hansen, and published last year in the journal Science, that the decades of peak nuclear deployment generate two to ten times more electricity than did peak decades of solar and wind deployment.

Why are we surprised that solar and wind generate so little power? Recall that their feeble output was the justification that anti-humanists Heidegger, Lovins and Ehrlich gave for using them.

Atomic humanists like Sting disagree with their dystopian low-energy vision. After he changed his mind about atomic power, he told Rolling Stone last year, “If we’re going to tackle global warming, nuclear is the only way you can create massive amounts of power.”

If renewables don’t generate very much power, then their environmental impact must be minimal, right?

On the contrary. Because sunlight, wind, water and wood are so energy dilute, their use requires far more natural resource than either fossil fuels or nuclear. Wind and solar require 17 to 35 times more land on average than does nuclear.

What about mining and waste? Solar panels require about 15 times more materials in the form of steel, glass, cement and metals than does nuclear per unit of energy. And solar creates 300 times more toxic waste than does nuclear, per unit of energy.

4.

The response from the nuclear establishment to the war on atomic power has been feeble at best and counterproductive at worst. In particular, solidarity is lacking.

As nuclear plants close around the world, celebrity scientists and philanthropists not only refuse to lift a finger to save nuclear, they go further and disparage the precious few operating reactors we have as dirty, dangerous, and expensive in contrast to the reactors that exist in their minds.

As such, they have fallen prey to the same arrogant techno-fix mentality that confuses demonstration reactors with first-of-a-kind commercial plants and thus results in serial design changes, construction delays, and cost-overruns.

And like a battered child seeking forgiveness for crimes she didn’t commit, many nuclear advocates seek peace and harmony with those who have never wavered in their lust for the extinction of atomic power.

So where do we go from here? Back to basics — back to atomic humanism.

What is atomic humanism? Love of our fellow humans. Love of nature. Love of reason.

But it has to become more than that still. We atomic humanists must become active. We must become democratic.

South Korea’s nuclear establishment showed how it’s done.

When South Korea’s anti-nuclear president declared that a 471-person “citizens jury” would decide the fate of two nuclear reactors under construction, Korea’s nuclear scientists went to court to stop a process they viewed as dangerous.

But experts could never decide such a matter due to the simple fact that energy experts don’t agree. Case in point is South Korea’s anti-nuclear energy minister who also happens to be a scientist and expert.

As importantly, people don’t want to be ruled by scientists and experts for good reason.

South Korea’s nuclear professionals lost in court. It was a blessing in disguise. Nuclear scientists like Professor Bun-Jin Chung were forced to engage their fellow citizens as equals.

And they did so brilliantly, making a calm and well-reasoned case for nuclear against the hysterical and irrational one made by anti-nuclear groups. Nuclear is the safest way to make energy, they explained. Nuclear energy prevents the spread of weapons. And only nuclear energy can lift all humans out of poverty while protecting the natural environment. As such, nuclear has transcendent moral purpose.

As a result, South Korea’s atomic humanists won in a 60 to 40 percent come-from-behind landslide victory, which has crippled President Moon’s nuclear phase-out.

Last Friday, I had the great honor of awarding Professor Chung the James Hansen Courage Award for his masterful closing argument to the citizens jury. Now, I look forward to awarding many more of these awards to atomic humanists around the world as we save the world’s nuclear plants from the forces of darkness.

5.

In the end, Heidegger was as wrong about renewables as he was about the Nazis, to whom he pledged his allegiance shortly before betraying his Jewish mentors.

That doesn’t mean his famous essay is empty of wisdom. At the climax of “The Question of Technology,” he quotes the 19th Century poet Friedrich Holderlin.

“Where the danger lies

so too grows the saving power.”

So, where does the danger lie? North Korea. Her people need nuclear power. We should give it to them. Even should North Korean Chairman Leader Kim Jong-un give us nothing in return, we have a moral obligation and sacred duty to, in the words of a great man of peace, “find the way by which the miraculous inventiveness of man shall not be dedicated to his death, but consecrated to his life.”

May peace be with us all.

As-salāmu ʿalaykum.

Thank you.