Pro-Nuclear Now: Why My View Changed, And What I Learned Along the Way -- Part 1

June 18, 2018

By Frank Jablonski

What I think about a lot.

I have, for a long time, been thinking about three important interlinked crises. I put them in these general categories: 1) energy and climate, 2) human development and well-being, and 3) ecosystems and biodiversity.

Protection of the climate requires drastic reduction or elimination greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions from the energy system.

Development adequate to provide a decent standard of living for everyone requires a sufficient supply of energy.

Preserving ecosystems and biodiversity requires us — the species that, in the formulation of Stewart Brand – are “as gods here” — to preserve and enhance the planet’s environments.

Overall, the challenge that rivets my attention involves making things better for people while protecting, restoring and improving ecosystems.

These crises have a moral dimension. The moral dimension gives rise to responsibilities. Meeting the responsibilities requires rigorous thinking. Rigorous thinking is logical, fact-based, and informed by the most reliable science we can find. This is the only way to make it more likely we will make the right choices.

It is no foregone conclusion that our problems will be favorably solved. We are not living in some Hollywood movie where Spielberg gets to deliver, at the last minute, the satisfying happy ending we want to see. If the script for this story is being written by our current choices, we are writing a script with an ending we don’t want to see.

Beginning.

I was standing over my bike at the traffic light where my bike path intersects a four-lane street. It was probably late April or early May of 2003. It was a soft mid-western mid-spring morning — the kind with warm sunlight, mild humidity, and cool air. An SUV drove past with an endangered species license plate with a wolf logo on it. Buying endangered species plates sends some money to the related wildlife programs. It’s a good thing to do. Then another vehicle, and then a third, all with the plates, which was a little surprising even for my neighborhood. Some drivers might have been people I know. I noticed each vehicle carried just one person.

The year 2003 was 24 years past the “No Nukes” concerts that seemed to confirm, in an emotionally compelling way, how everyone who was sincere, good, and committed to a better world would be absolutely, unalterably, and categorically against nuclear energy and in favor of renewable energy “instead”.

It was fifteen years past James Hansen’s climate change testimony to congress (1988), eleven years past the UNCED Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit (1992), six years past adoption of the Kyoto Protocol (1997), and 89 years past the Popular Science article that had posited it to be “highly probable” that “a few years hence” “solar engines and solar heating apparatus will then make it economically practicable for us to use at least a small portion of our now wasted sunshine to run our factories, light our streets, cook our food, and warm our houses.” (October, 1934).

It was also eight years past the release of a study titled “The Green Plan: Energy, Jobs, Opportunity and Economic Development for Wisconsin” (where I live) (1995). I was the document’s organizer and lead author. It was sponsored by the state’s lead environmental and renewable energy advocacy organizations, Wisconsin’s Environmental Decade (predecessor to the current Clean Wisconsin) and RENEW Wisconsin. The Plan posited that Wisconsin’s energy needs could be met by expanding the use of renewable energy and by constraining demand through energy efficiency and conservation. You will see policy prescriptions touting the same theory now, 23 years later.

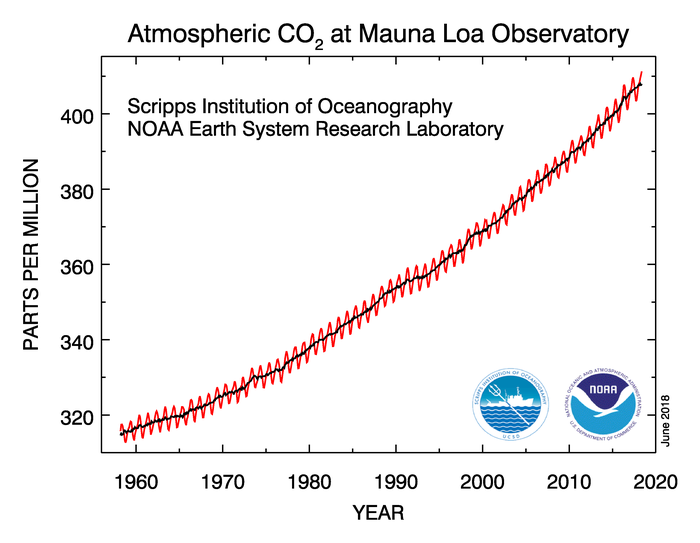

By that spring morning in 2003, carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere had risen by about another 10 parts per million (ppm) from when we released the Green Plan, from about 360ppm to more than 370ppm. They now exceed 400.

Greenhouse gas concentrations and their effects were a thing we were pouring our energies into doing something about. Our belief that the dangers posed could be avoided by improving efficiency and using renewable energy didn’t matter. The numbers continued to go in the wrong direction. We were not doing very well. We still aren’t.

A decision out of character.

The SUV with the wildlife license plates stuck in my mind as a kind of reminder or reality-check. People sensitive to wildlife — people who probably thrill to the natural landscapes here, to the sight and sound of wild geese in the sky, to the feeling that you get when light pours through breaks in the pine forest, to the sparkle of hard sunlight bouncing off lakes, to the sound of cool streams, alive with life, flowing over old rocks – people who view themselves as deeply committed to environmental responsibility and pretty much in love with nature were still going to drive SUVs, drive alone, live in houses, fly places in airplanes, and, generally, live developed-world lives of high energy consumption. People are not going to erase civilization and its comforts because they are concerned about climate.

Although I am not an SUV owner, I certainly fall into that category. If I had some kind of greenhouse gas budget – though it seems like that budget would ideally, and impossibly, be “0” – then any gains from my bicycle commuting would certainly be spent out, and then some, by flying. Marginal or even dramatic changes to energy efficiency were not mattering. Fast growth in small contribution energy resources like wind and solar weren’t mattering either. Taken together, they were nowhere close to canceling out the relentless year-over-year growth of greenhouse gas concentrations. (They still aren’t.) It doesn’t matter how many photos of wind turbines and solar panels appear on utility Company websites. It doesn’t matter the number of articles enthralled journalists write to proclaim the imminent arrival of the renewable energy paradise, or how many people are seduced by sunny narratives they ardently want to believe. Small changes don’t amount to much against the scale and scope of the problem.

The notion came to me that, in the interest of doing something about climate, I at least ought to think about whether nuclear energy should be re-considered.

This idea was “out of character” to the degree I was, and mostly remain, pretty much your standard-issue environmentalist. I was president of a high school club that started a city-wide recycling program in the 1970’s and was named the state’s “Outstanding Young Conservationist” the year I graduated high school. My first position out of law school was with the state’s largest environmental group. I felt at the time, and still recognize, that it was a privilege to get that position. I was able to represent the aspirations of a community of committed people I deeply respected.

So, I was part of the mainstream environmental movement. The same movement that has stoked fear of nuclear energy and done everything it could to stop nuclear energy and drive up its costs. Curiously, it wouldn’t have had to be this way. Environmentalists could have advocated for deployment of nuclear to displace coal and its emissions for optimal operation of existing plants, and accelerated development of improvements to address the technologies’ issues. But that is not how it worked out. Some roots of the movement and the evolution of its position and strategies on nuclear energy, are described (unsympathetically) here and here.

The motivations I observed seemed purer than portrayed in the links in the previous sentence, but I witnessed those sentiments as well. I also saw activists who were willing to endure large personal sacrifices in the interest of what they believed to be right. To work long hours, to get arrested, to live without much money or security. While some individuals had resources, overall, we were badly outnumbered, under-resourced and often poor. Since fear was so entwined with the choices we made on nuclear, using fear to convince others seemed more than appropriate. It seemed imperative.

My first appearance in court as a lawyer was to try to shut down a nuclear power plant by opposing replacement of its electrical generation equipment. I was “all in” with unwavering opposition to nuclear power. I worried about melt-downs and radiation and nuclear waste and proliferation.

But in 2003, eight years after the Green Plan, I could no longer ignore that the renewable energy and energy efficiency improvements we advocated were failing to accomplish much on climate. The idea that I should at least re-think the nuclear question would not go away. So, I started to restudy my many objections. It took a couple of years. This series of short essays is about what I learned in that re-study, and how it changed my mind.

“Deadly radiation.”

I believed the actual and potential radiation impacts of nuclear power plants posed potent, unacceptable hazards both to our health and, through genetic impacts, to future human generations. These shared beliefs were hardwired. They justified labeling nuclear energy “poisonous”, and they animated our determined and relentless opposition. Since this was a core issue, a lot of my initial re-study of nuclear energy focused first on radiation.

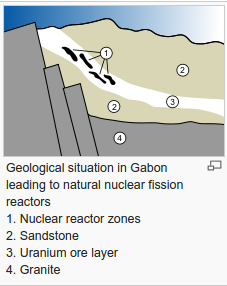

Studying the issue with the best science I could find destroyed my fixed beliefs. Radioactivity is an unavoidable property of our world and a common phenomenon in our bodies. Across time – geological time – the levels on our planet have fallen, because radioactivity is a type of activity that wears away under most conditions on our planet. Background levels of radiation were much higher in the past than they are now. Natural nuclear reactors under the surface of the earth operated for hundreds of thousands of years as life evolved. Our planet, and everything and everyone on it, derive from nuclear reactions in supernovae explosions long ago. Without radioactivity we would not exist.

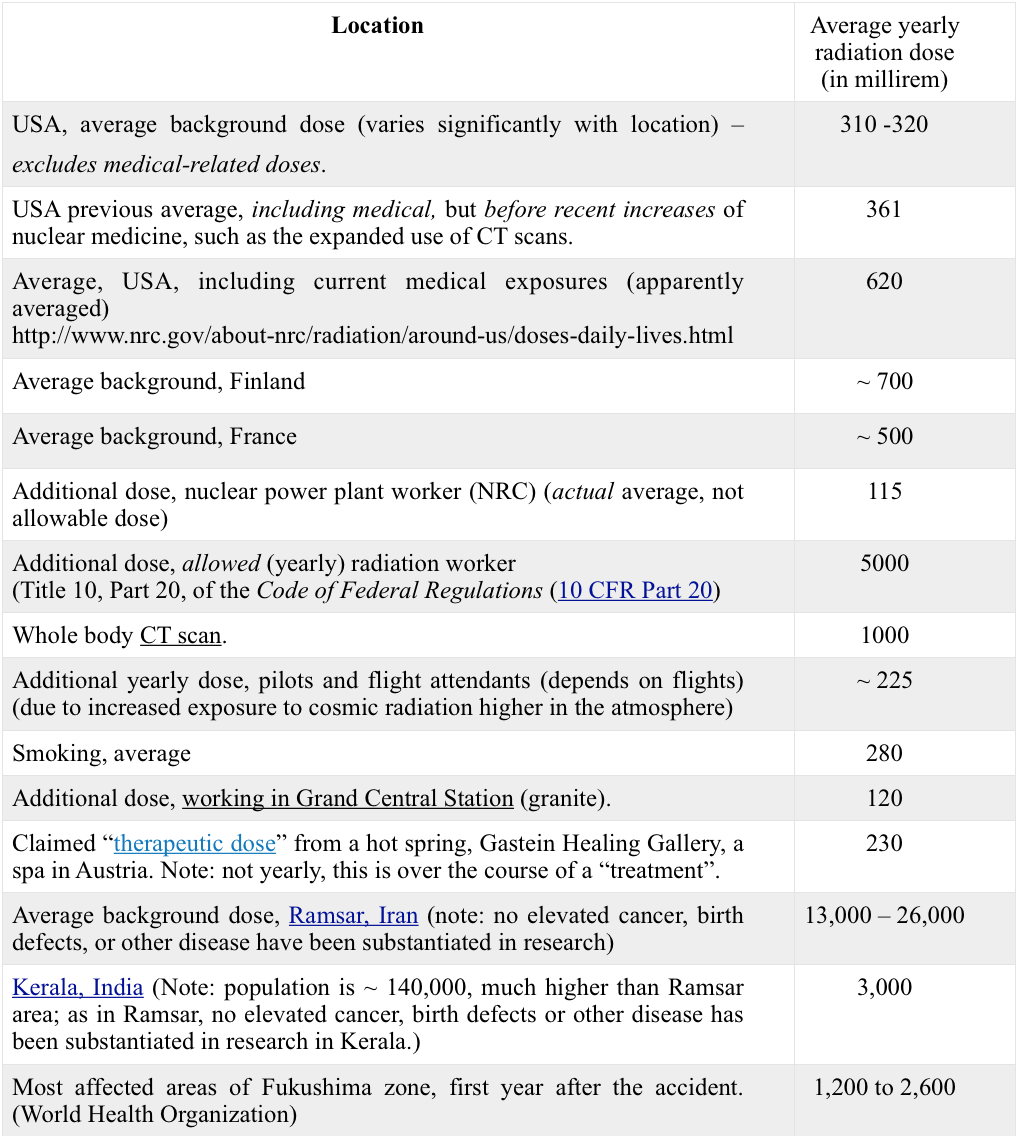

I quickly found some numbers I had never really thought about: the average additional exposure to radiation that Americans experience from background sources is about 310 - 320 millirem, although I also saw it “officially” estimated at 360 millirems – a number that I believe included averaged radiation exposures from medical procedures before CT scans became as common as they are now.

For comparison’s sake, the additional average radiation exposure of Americans due to commercial nuclear power operations is less than 0.1 millirems/year. This means that the average exposure from commercial nuclear energy is about 1/3100th of your average background dose. One part in three thousand one hundred. A 1991 study by the National Cancer Institute, "Cancer in Populations Living Near Nuclear Facilities," concluded no increased risk of death from cancer for people living in counties adjacent to U.S. nuclear facilities.

On average — obviously averages don’t work all that well here, since cancer patients undergoing treatment will be exposed to a lot of radiation while luckier people just have occasional dental x-rays — this 0.1 millirems exposure is also about 1/3100 of an American’s medical exposure. The average medical exposure has gone up since CT scans became more common. Now it approximately doubles the average background exposure.

I found this interesting: about 1/8th of the average person’s radiation exposure (39 millirem/year) is from radioactive decay inside the body. Our bodies have, and continuously take in, traces of naturally occurring radioactive materials, mostly radioactive nuclides present in food and in the air. For example, 40K (Potassium 40) is a radioactive isotope of potassium, an element that is essential to life because it aids transmission of electrical signals within our bodies. We get it from many foods, with notable amounts available in bananas and brazil nuts. That potassium, along with tritium (3H) and carbon-14 (14C) contributes to the approximately 4,000 - 5000 radioactive decays of individual nuclei every second in a person’s body, assuming a 175 lb. person. (Some sources estimate the number of decays higher, e.g., 8,000).

Over the course of a week, these decays within your body add up to about 2/3 of a millirem of exposure. Very little of the usual exposure to radiation comes from any source other than background sources, the exception being if someone is using nuclear medicine, e.g., radiation therapy for cancer or diagnostic medical procedures (e.g., x-rays and CT scans) that use radiation. Background sources – principally radon created as a result of radioactive decay of materials common in the earth’s crust, and gamma rays from space – are far more significant sources of radiation exposure.

I also found occupational exposures interesting. The average additional exposure of a person working in a nuclear power plant in the US is about 101 - 115 millirems per year. By comparison, the additional dose that you would get as a full time worker at Grand Central Station, whose grandeur comes from granite that incorporates naturally radioactive material, is estimated to be about 120 millirems.

That's right. Your average occupational radiation exposure is higher if you work in Grand Central station than if you work in a nuclear power plant.

If you have natural gas service in your home, your average exposure from having it is about 9 millirem/year – 90 times higher than the average American’s radiation exposure from commercial nuclear power operations. The 4 – 5 millirems of radiation you get from flying cross-country is 40 to 50 times more than the radiation the average American gets from commercial nuclear energy. Flight-related exposure is due to exposing yourself to more cosmic radiation from space from being up in the sky.

The greatest variation in radiation exposure arises from differences in background radiation. On the high Colorado Plateau, as compared with the Midwest, you expose yourself to higher levels of cosmic radiation from space and from isotopes that are part of the soil and the rocks there. There, you are exposed to about twice the background radiation you experience in the Midwest.

In contrast with the average dose actually received at nuclear plants (101 to 115 millirems), the allowable dose for radiation workers is 5,000 millirems – half the level (10,000 millirems or 10 rem) at which scientists are able to discern organism-level radiation effects on people. Below the 10,000 millirem (10 rem) level, adverse organism-level effects on people, if any, are not able to be separated out from other potential causes of the same effect.

Here are some radiation-exposure comparisons:

Some key implications of the table: staying on popular tourist beaches in Brazil would expose you to a dose of radiation about 50 times the average background radiation in the United States. Exposures from background sources in Kerala, India, and Ramsar, Iran, are 40 to over 85 times the average exposure in the USA. Spa treatments at hot springs expose people to high levels of radioactive radon.

Although my reconsideration of nuclear energy came before the Fukushima meltdown, it is notable that many background levels of radiation, which are elevated because of natural processes, greatly exceed the levels at remaining “hotspots” in Fukushima Province in Japan, and also exceed most locations in the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Finally, there is this weird thing: powerful data-based scientific arguments support the proposition that certain levels of radiation exposure stimulate immune response that, in turn, enhances, instead of impairs health – kind of like what vaccines do. A reasonably good general discussion of the associated theory is here. Some people are not waiting for the science to settle on this. Germany and Austria, both hotbeds of anti-nuclearism – have old mines with high levels of radioactive radon. Those mines are tourist attractions. We have them too.

The upshot: not so deadly, not so scary, not so different.

I worry about a lot of things. Radiation is no longer one of them. Radiation is a natural property of our planet, and its smart to think about the same way we think about other properties, substances or phenomena, i.e., to ask how can it be useful in a positive way, and how can we minimize or avoid potential harms. Human beings have been manipulating, concentrating and re-organizing this planet’s available properties, substances and phenomena for as long as we have been able. We manipulate, concentrate, re-organize and relocate minerals, salts, plants, heat, water, energy, nutrients– pretty much anything we can exert control over. We do it to make things fit our needs and it is our job to manage the things that we manipulate so as to minimize or avoid damage to ourselves, others and the environment. Radiation is one of the things we have to manage. Overall the civilian nuclear industry has managed it remarkably well. It merits care, not fear.