Be Like Marie: Why Women are the Breakthrough Nuclear Needs

Speech to Women in Nuclear, Canada, September 27, 2018

By Michael Shellenberger

1.

Let’s start with the bad news: nuclear power is in decline. As a share of electricity globally, nuclear peaked in the mid-1990s at nearly 18 percent. Today it is under 10 percent. As total generation, nuclear peaked in the mid-2000s, a half decade before Fukushima, which reduced it further. Now we are at risk of losing twice as much nuclear as we add over the coming decade.

The reason is obvious: people don’t like it. In a recent worldwide survey, just 28 percent of respondents said they had a favorable view of the technology in comparison to 60 percent for natural gas and 85 percent for solar. Nuclear is viewed as above average only in reliability, when compared to other energy sources, and below average on every other metric including safety, trustworthiness, and environmental friendliness. In the U.S., support for nuclear is at an all time low. Just 44 percent support it, which is 18 points less than its peak of 62 percent in 2010.

Women are the main cause of nuclear’s unpopularity. In the U.S., 74 percent of men support it but only 45 percent of women. Now, you might be thinking: Canada is different — and you would be right, but only in part. Ontario is the sole province where nuclear has majority support, and only barely, at 54 percent. In every other province, the majority is opposed. The 30 point gender gap in Canada is identical to that in the United States. And after the 2011 Fukushima panic, support for nuclear among men remained steadfast but declined among women.

The reason for nuclear’s low support seems obvious: around the world, people think it’s dangerous — including in Canada, where 55 percent believe the word “dangerous” describes nuclear very well or well — more than any other.

But is it? Not in comparison to other energy sources. In fact, according to the most comprehensive and recent study, published in the British medical journal Lancet, nuclear power is the safest way to produce reliable electricity.

Even unreliable forms of electricity, like wind turbines, are more deadly than nuclear, resulting in myriad deaths like of these two maintenance workers in Denmark who huddled together before they were killed by fire, and falling, in 2013, shortly after this video was taken.

Nuclear doesn’t contaminate the air, and air pollution results in the premature deaths of seven million people per year. As a result, nuclear has saved at least 1.8 million lives that would have been lost to pollution. But obviously, facts like these don’t matter enough because if they did, nuclear should be the most popular rather than least popular energy source.

There is more than 40 years of study into nuclear’s gender gap. At first it was thought women were less informed than men. This turned out to be incorrect. Tellingly, nuclear is less popular with female scientists than it is with male scientists.

Social scientists then blamed the disempowerment of women relative to men. Support for this hypothesis came from the fact that various studies found that other demographic groups, particularly racial minorities, demonstrate similarly low support for nuclear. Scientists have explored two reasons for this: that less powerful individuals have less to gain from the system nuclear is perceived to be a part of, and/or less powerful individuals are more fearful in general.

There is no doubt some truth to these hypotheses, but they aren’t the whole story. A recent survey found that where 60 percent of whites support nuclear, so do 58 percent of Hispanics, which is within the margin of error, and 50 percent of blacks. While that 10 percentage point gap is significant gap, it is still just one-third less than the nearly 30 percentage point gap between men and women

What gives? Why is nuclear so unpopular in general, and unpopular among women in particular? To answer those questions we have to go back in time — back to the rise of nuclear fear.

2.

In 1962, the Executive Director of the Sierra Club asked a young man working for him to investigate a site in northern California where the electric utility wanted to build a nuclear plant. After the young man, David Pesonen, spent the day there, he had an epiphany. “It was a turning point in my life,” he recounted later. “I had a feeling of the enormousness of what we were fighting; it was anti-life. I began to see it as the ultimate brutality, short of nuclear weapons.”

On his return, Pesonen told the Sierra Club’s board of directors that he could stop the plant’s construction, but that typical conservationist arguments wouldn’t be enough. To win, they would need to convince the local people that radiation from the plant could contaminate them and cause cancer. Pesonen was inspired by growing public concern with the radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing, which had been making its way into the teeth of infants.

The ground was being prepared for their campaign already. In 1956, half of media stories about peaceful nuclear power in the U.S. had positive titles while the other half were neutral. Four years later, just one-quarter of the titles were positive.

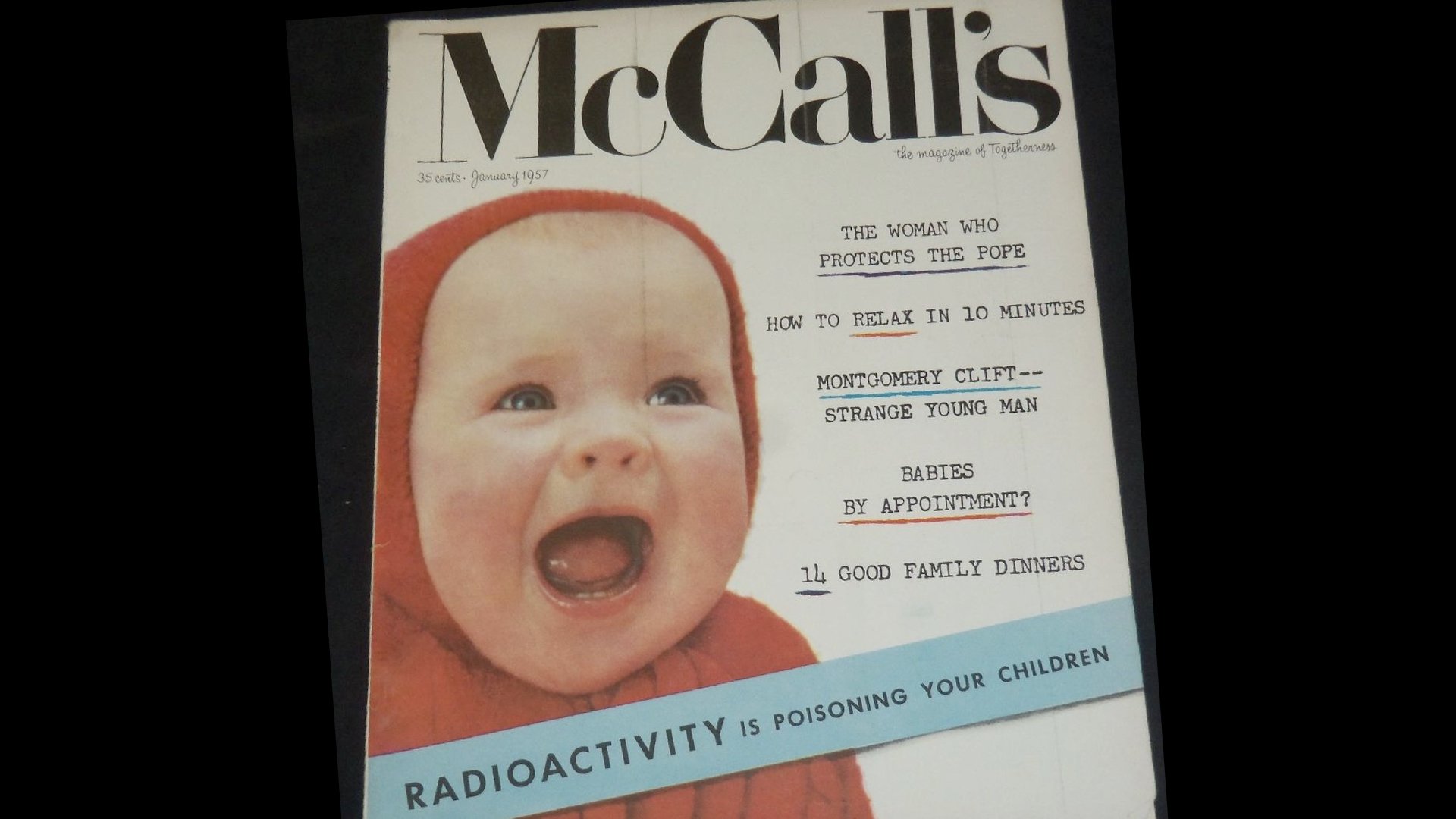

A big part of the reason was weapons fall-out. “Radioactivity is poisoning your children,” read a banner splashed across the cover of a January 1957 issue of McCall’s, a leading women’s magazine (another headline on the cover, next to the wide-mouthed baby, was, read, apparently without irony, “How to Relax in 10 Minutes.”)

Four years later, the journal Science published an article documenting how levels of strontium-90, a radioactive isotope produced by weapons testing, were 50 times higher in the teeth of children born during nuclear weapons testing than before. It was still 200 times less than the levels known to cause cancer, but the study still generated headlines, and alarm, worldwide.

In response, parents — and mothers in particular — demanded that President John F. Kennedy negotiate an end to weapons testing with the Soviet Union, which he did two years later. Banning weapons testing became a cause celebre for the burgeoning women’s movement. “Men have always played irresponsibly with human life,” wrote Midge Decker in an article for Harper’s in 1963, “while women have always protected it.”

Even so, the Sierra Club’s male-dominated board of directors was taken aback by Pesonen’s proposal to frighten the public about the risk of radioactive fall-out. “Don’t you dare mention public safety,” one of them warned Pesonen. “The Sierra Club can talk about scenic beauty, and maybe the loss of scenic beauty, but not about public safety. That’s not our job.” Few Club directors had any problem with nuclear plants per se. Several were, in fact, advocates of it, seeing nuclear as the best alternative to burning coal and oil, or damming rivers for hydroelectricity. Another Sierra Club director called Pesonen an “extremist.”

And so Pesonen quit and started a new organization. His two main allies, Hazel Mitchell and Doris Sloan, were women. Together they produced and distributed a report claiming that the proposed nuclear plant would create “death dust,” nuclear fall-out, that would contaminate the local milk. They attached notes to 1,500 helium balloons, and released them. The notes read, “This balloon could represent a radioactive molecule of Strontium-90 or Iodine-131. Tell your local newspaper where you found this balloon.” The local dairy farmers, alarmed by the apparent danger, if not to their milk then at least to their businesses, started donating money to Pesonen’s cause.

Until then, fears of radiation from nuclear had been largely confined to weapons, not energy. By linking the two they tapped fears, especially strong among mothers, that their children could be poisoned, and eventually won the day. “If you’re trying to get people aroused about what is going on,” Sloan explained later, “you use the most emotional issue you can find.”

3.

By the end of the decade, the anti-nuclear faction had taken over the Sierra Club. Fear of radioactive contamination had trumped fears of air pollution. The environmental organization was soon joined by Ralph Nader, the consumer advocate, and a new group, Friends of the Earth, founded by a former Sierra Club Executive Director “[A] million people,” he claimed, “die in the Northern Hemisphere now, because of plutonium from atmospheric [weapons] testing.” Said Nader in 1974, ”A nuclear accident could wipe out Cleveland, and the survivors would envy the dead.”

Nader brought anti-nuclear leaders from around the country to a Washington, D.C. and trained them on his take-no-prisoners style of play. The same year, the new head of the Sierra Club wrote a strategy memo to the board. “Our campaign stressing the hazards of nuclear power will supply a rationale for increasing regulation,” he wrote, “and add to the cost of the industry.”

Over time people came to describe and think of nuclear weapons, energy, waste, and fall-out as contaminations of nature generally, and the body specifically. “Thoughts about waste had unmentioned resonances,” notes the historian Spencer Weart in his essential study, The Rise of Nuclear Fear.

“When some critics called radioactive wastes “sewage” they were suggesting thoughts of excrement. The nuclear industry itself described its wastes as products of the ‘back end’ of nuclear fuel processing… industry workers described radioactively contaminated objects as “crapped up” while a psychological study found the word ‘wastes’ evoked disgust.”

Linguistically, foul words for excrement are used in anger to express anger. The father of the atomic bomb, Robert Oppenheimer once said “The atomic bomb is shit,” because it is not good for anything. “[O]n every level of human thought,” Weart concludes, “radioactive wastes — in association with weapons — were seen as filthy insults against the proper order of things.”

In other words, the public came to see nuclear as dirty only after it saw it as dangerous, and thus immoral. ''The critics of our society are using nature in the old primitive way: impurities in the physical world or chemical carcinogens in the body are directly traced to immoral forms of economic and political power,” wrote anthropologist Mary Douglas, who analyzed anti-nuclear activists the same way she did other cultures. “Laws of nature are dragged into sanction the moral code.”

Disgust, psychologists remind us, is a deeply primal emotion. We've all had the experience of triggering it. My wife and I were at a restaurant in Oakland, California recently, and fell into a conversation with a friendly couple next to us. They were in the restaurant business and, after my wife described what she did, it was my turn. No sooner had I said, “nuclear —“ than they both nearly shouted with agony, “Oh, god! Don’t say that word!” as though they wouldn’t have reacted so strongly had I called it atomic power instead. They seemed angry at me for having contaminated their dinner.

What happened next was that nuclear’s alleged danger was displaced, psychologically, first from nuclear bombs to nuclear plants and then to nuclear waste, as we might displace our upset at our boss onto our spouse. Writes Weart:

All the elements of classic displacement were indeed present. There was persistent anxiety about nuclear war. There was an inability to dispel the anxiety in the only genuine way, by getting rid of the bombs. Finally, there was a target toward which the frustrated feelings could redirect themselves, and all the more easily because of many of the associations between bombs and reactors

Women have good reasons to be more sensitive to bodily contamination than men. Even before the science of radiation women have known intuitively for thousands of years that their children, particularly those in utero, are uniquely vulnerable to contaminants that could threaten their health and even lives. We shouldn’t be surprised, then, that by the late 1970s, women anti-nuclear leaders came to be so influential.

One of them was Jane Fonda, one of the most powerful people in Hollywood. In 1979 she produced and starred in “China Syndrome,” an anti-nuclear blockbuster that depicted nuclear accidents as apocalyptic and triggered a nationwide panic when a reactor in Pennsylvania melted down (hurting nobody), just 12 days later. In a documentary-style interlude in the middle of “China Syndrome,” Fonda showed mothers speaking out at public meetings to halt nuclear plants — just as Nader and the Club were organizing activists to do across the country.

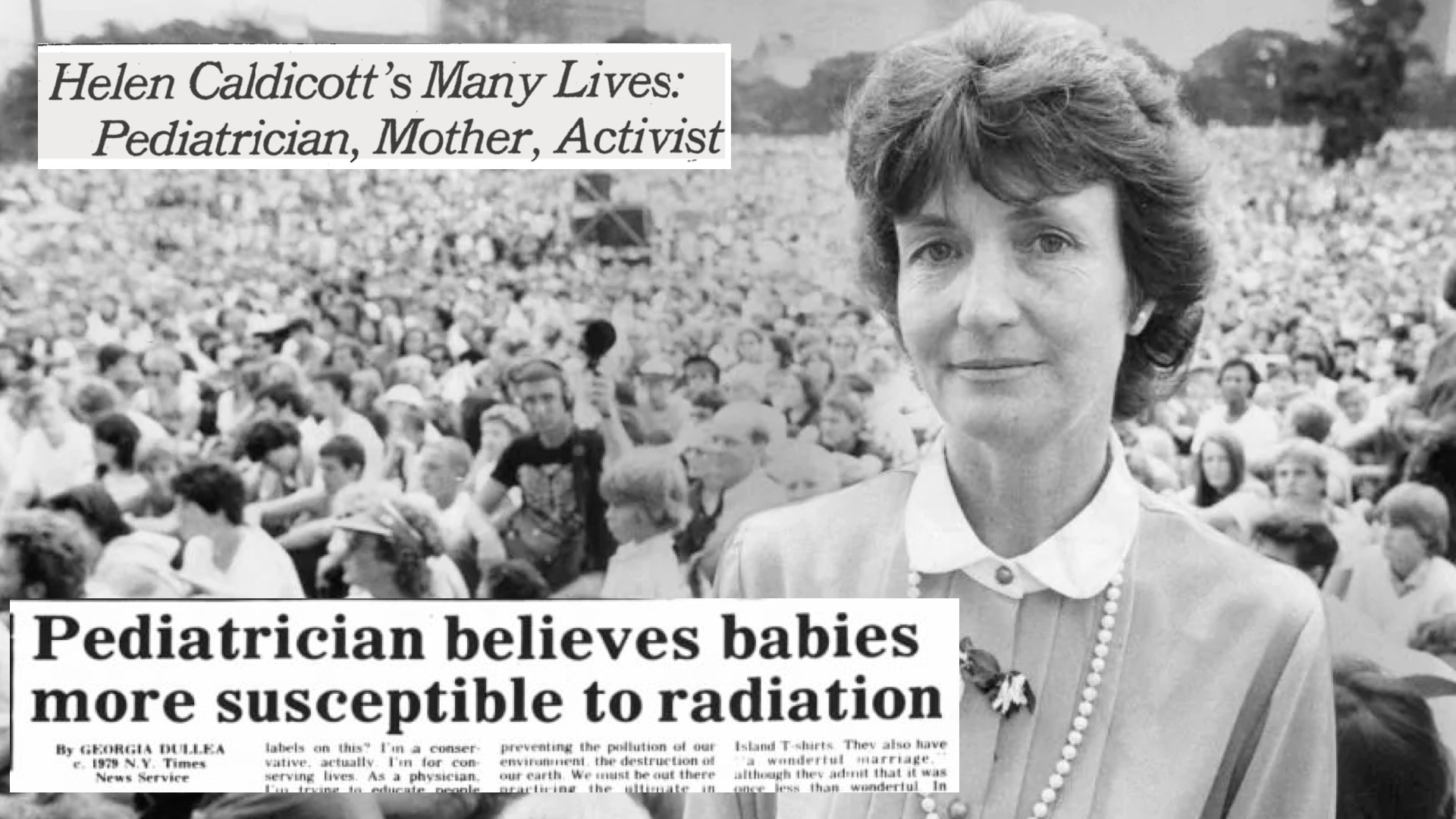

Another was Helen Caldicott, an Australian pediatrician who became famous for her advocacy with Dr. Benjamin Spock, the child-rearing expert, in the 1970s. Warm, emotional, and seemingly qualified, Caldicott had a flair for the dramatic. At a 1979 No Nukes rally, Caldicott carried a black coffin with a sign that read, “Babies Die First.”

Fetuses, babies and young children are 10 to 20 times more susceptible than adults to the effects of radiation,” she told thousands of people. What drove her? She had read the 1957 novel, “On the Beach,” about a nuclear war set in Australia. “It frightened the hell out of me,” she told The New York Times, in a fawning 1979 profile. “I’m still frightened.”

Caldicott’s power, The Times explained, came from the fact that “She spoke not as nuclear scientist but ‘as a pediatrician, a mother and a world citizen.’ The headline of The Times read, “Helen Caldicott’s Many Lives: Pediatrician, Mother, Activist.” But the regional newspapers that picked up the Times story gave it a blunter headline: “Pediatrician believes babies more susceptible to radiation.”

It was the 1979 meltdown at Three Mile Island, and resulting panic, that pushed her into the mainstream. “The unflinching face and urgent voice of Helen Caldicott was all over the television screen,” said the Times. The Times article kept stressing the crucial point: Caldicott wasn’t just a qualified, as a pediatrician, she was active and engaged as a mother.

“We cannot remain in our laboratories, our hospitals, our offices anymore,” she said. “I'm learning to teach people through love, not hate…. What I do now is to appeal to their goodness as human beings on the radiation issue. They've got children, they've got bodies. I try to appeal to their emotions… Have the people who build these weapons ever seen a child die of leukemia? I have.”

Wait, weapons? I thought we were talking about nuclear power? The two were constantly, and easily, being conflated. Just have a look at the poster advertising the No Nukes concerts, initiated shortly after Three Mile Island. Supposedly it was aimed at nuclear energy. But in the background looms a mushroom cloud with very nearly the same menacing shade of orange used on the poster promoting “The China Syndrome.”

Their campaign worked. By the 1980s, 150 percent more nuclear power was cancelled or killed than was built.

4.

A big part of what gave the anti-nuclear movement its energy, and later its credibility, was the notion that nuclear energy wasn’t needed. "All of the solar energy technologies that can replace fossil fuels are in hand, some are already economically competitive with conventional sources, and many are rapidly approaching that point,” anti-nuclear leader Barry Commoner said in 1975.

In the meantime, anti-nuclear activists decided fossil fuels were better. “Unlike nuclear, which risks long-term genetic damage,” said one Sierra Club leader in 1974, “coal’s impacts won’t be felt generations from now.” Over the next 45 years, renewables would be promoted and depicted as a way to harmonize human society with the natural world.

Nuclear even more than fossil fuels represented humankind’s break from the natural order — something the nuclear industry itself has promoted with with its depictions of nuclear in dehumanized industrialized landscapes rather than in its natural ones.

In one way, the nuclear industry responded to Three Mile Island and the anti-nuclear movement exceedingly well, improving safety and performance. It improved worker training, worker-machine interfaces, and management techniques in order to reduce unplanned outages. It shortened planned outages, in ways that lifted capacity factors — the share of the year nuclear plants operate — from 55 to over 90 percent. These measures demonstrated not only that the nuclear industry was responsive to public concern but also that safety and profitability go hand-in-hand.

But in other ways, the male-dominated nuclear industry let its technocratic approach run ahead of the humanism that had characterized the vision of Atoms for Peace. Nuclear scientists in universities and laboratories promoted the idea that radically different reactor designs, smaller reactors, or thorium instead of uranium, would yield some kind of safety advantage that would also translate into lower costs.

In reality, large water-cooled nuclear designs remain the safest and cheapest form of nuclear, after decades of experimentation, for the simple reason that they are what we have the most experience building, operating and regulating. Worse, advocacy of radical innovation reinforces the sense that there is something fundamentally wrong with nuclear energy.

Similarly, efforts by the nuclear industry to distance itself from nuclear weapons haven’t worked. The public — especially those further to the left, politically — continues to associate the two, albeit mostly unconsciously. Over the last few years, after I publicly changed my mind, I’ve benefited from friends and acquaintances admitting to me that they couldn’t get over their fears. “I just keep seeing a child burned up,” said one acquaintance, referring to the documentary film Hiroshima. When I explain that nuclear plants can’t explode like weapons, they all nod in agreement. Their rational minds get it. But as everyone knows, our rational minds are often subservient to our irrational unconscious.

A better approach, in my experience, is to point out that our fears of nuclear weapons turned out to be unfounded. Humankind is further from the use of them at any point over the last 70 years. Just as we got better at operating nuclear plants we got better at safeguarding nuclear weapons. The close calls, none of which were as close as anti-nuclear publicists have claimed, were in the early decades after their invention.

Most of all it’s impossible not to be struck by the evidence showing that deaths from wars and violent conflicts around the world increased steadily from 1400 until 1945 and then plummeted. Even those who emphasize other factors for declining violence — whether the rise of the United Nations, greater prosperity, or better education — must acknowledge that the great peace has occurred simultaneous to the spread, not containment, of nuclear weapons.

In any event, nuclear weapons aren’t going away. Indeed, they continue their slow spread. Nations that feel threatened, whether North Korea or Iran, understandably seek to acquire them, despite strenuous efforts to prevent them. The vast majority of nations don’t need them, either because they, like Western Europe, Japan, and South Korea, are under our nuclear umbrella, or because they, like Canada, face no external threat.

My own attitude is that we need to grow up. The world is full of dangerous things we either can’t or don’t want to get rid of. Many of them — including the polio virus, which we could have destroyed permanently, is now being developed into cancer treatment — have proven enormously useful. Dangerous things aren’t “immoral.” That’s a child-like view.

Having said as much publicly, I was taken aback by how upset many people became in response. But the upset only reinforced my belief that fear of weapons is the x-factor behind continuing public opposition to nuclear energy.

I acknowledge that overcoming fears of a nuclear-armed world won’t be easy, and will take time. But it will be far easier than persuading the human race of something untrue — that the desire for nuclear energy and nuclear weapons are unrelated — or that we will or should eliminate weapons, which no nation which has them has ever shown any serious interest in doing.

5.

What does all of this mean for women in nuclear?

First, you are on the right track in being organized as women. It’s not just that the nuclear industry is male-dominated. It’s that nuclear power’s womanly and motherly energy isn’t being felt by the public. Nuclear industry leaders — intimidated by an understandably emotional public — too often retreated into their machines when they needed to lean into, and invest in far more into, humanistic public engagement. It’s not just that we need more women in nuclear. We need a women-led — and womanly — nuclear.

That means a far more prominent role for mothers, not just women, in your movement. “Women” connotes gender whereas “mother” connotes a relationship and a deeply primal one at that.

Mothers for Nuclear is a group started by two nuclear engineers, Kristin Zaitz and Heather Matteson, not public relations executives. They aren’t scared to use their children to talk about substantive issues. Why would they be? They’re speaking out for their children.

And they’re engaged. They recently went to Fukushima to meet with locals. One of them, Kristin, was pregnant at the time. While there, they ate the fish and the peaches, which are some of the best in the world. Why? Because they care, both about the people there, and about the future of nuclear. And they understand the science of radiation well enough to know that they were safe doing so.

Such humanistic actions speak louder than words. “People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care,” a wise man once said.

Second, stop hiding nuclear’s light under a bushel. The worst example of this is the World Nuclear Association’s promotion of so-called “Harmony” with renewables.

Nuclear is the best way of making electricity on every metric: public health, cost, land use, waste disposal, professional development — you name it. Consider that nuclear requires just six percent as many materials — concrete and steel — as solar. Which is why solar panels create 200 to 300 times more toxic waste by volume than the spent fuel from nuclear, and none of it is safely contained. Nor do the toxic elements including lead, cadmium, and chromium, become less toxic over time. Wind turbine blades are nearly as toxic.

In the name of harmonizing with nature, we are destroying it, spreading electronic garbage over landscapes in the name of Mother Earth. Where there’s no solution for solar panels and wind turbines after they become useless in 25 years — almost all of them will just go to the waste dump — nuclear pays to store its tiny quantities of waste, which never hurt a fly, permanent.

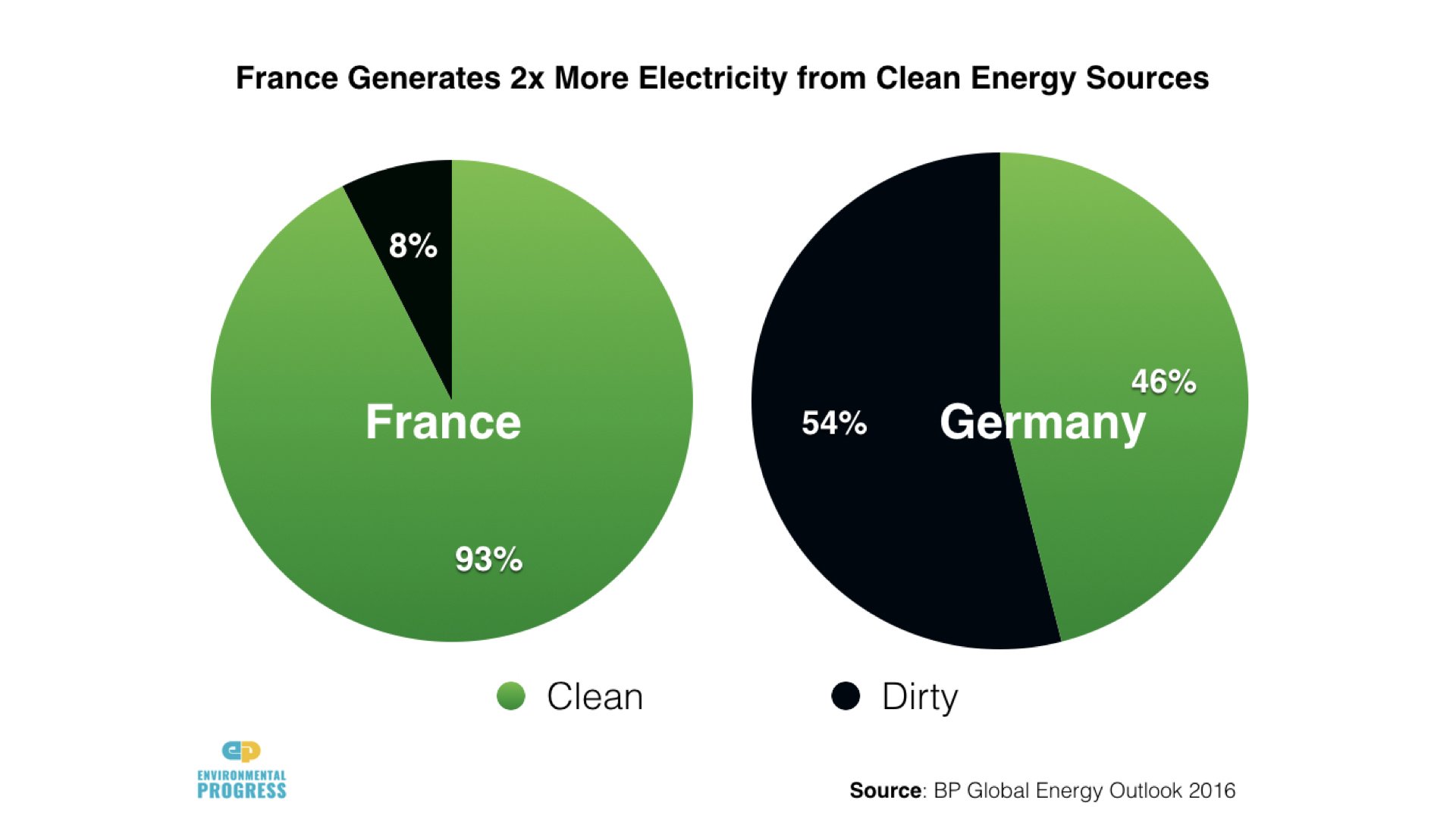

And what’s with pretending that we “need” solar and wind if we have nuclear? Adding solar and wind to a nuclear-heavy electricity mix in places like Ontario or France would also require increasing the combustion of natural gas. How is that a good idea, exactly? It’s not like solar and wind are promoting nuclear; on the contrary, the solar and wind industries promote the idea that we don’t need nuclear, as does the natural gas industry, by the way, which loves to greenwash with solar and wind.

And that’s just emissions. The impact on landscapes is even more dramatic. Even in sunny California it takes 5,000 times more land to produce the same amount of energy from solar as it takes from nuclear. Building solar farms in California’s mojave desert required killing our endangered desert tortoise, the state reptile. Wind farms in the U.S., meanwhile, are at risk of making the migratory white nosed bat species extinct. The only industry allowed to legally kill condors is the wind industry. Scratch the surface of solar and wind and you discover secrets and lies covering up wildlife impacts, which the two industries are usually not required to investigate much less report.

And there is no more powerful way to overcome the stigma of nuclear as dirty and polluting than to contrast it favorably to solar, wind, and fossil energy — a strategy disallowed by the nuclear industry’s Harmony ideology. This harmony ideology is a kind of learned helplessness the industry has developed as a result of the trauma of decades of anti-nuclear attacks.

Finally, let’s work together. Next spring, Environmental Progress, along with Kristin Zaitz, co-founder of Mothers for Nuclear, is hosting a meeting in Berkeley with nuclear energy leaders and change agents to plan a 10-year, international effort to engage the public and change how humankind thinks about nuclear. If you care about nuclear power beyond your job, and would like to be involved, please email my colleague, Madison Czerwinski, explaining who you are and why would you like to attend.

More than anything else we must Humanize nuclear. How? By being like Marie Curie. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and the first person, and only woman, to win two Nobel Prizes, one for physics, in 1903, and the other for chemistry.

But more important than any of her many recognitions, Marie Curie was the first atomic humanist. What’s an atomic humanist? Someone who puts the power of the atom in service of the the world, not herself. Her life exemplified her care, her courage, her passion, and her commitment.

Just three years after winning the Nobel Prize for physics in 1903 with her beloved husband, Pierre, he was run over by a trolley and killed. Devastated, Marie buried herself in her work. Eventually she took another lover — alas, a married one. She begged him to abandon his wife, from whom he was estranged, but his wife found out, and the ensuing scandal became front-page news across Europe.

After winning her second Nobel prize in 1911, the cowardly Nobel committee requested she not travel to Stockholm to accept it, fearing the negative publicity. Marie valiantly asserted her right to accept the award in person against the committee’s double-standard — plenty of adulterous men had likely been awarded prizes before her — and struck a blow for women’s rights.

Her greatest achievement was to put the power of radiation in service of humankind. When World War I broke out, she went to the French government with a plan: she would create and oversee, with her 17 year-old daughter Irene, 200 hundred mobile medical units — which would become known as “petites Curies” — to use x-rays to diagnose injuries and radium to sterilize infected tissue. She invented hollow needles containing "radium emanation,” a radioactive gas, now known as radon, to be used for sterilizing infected tissue.

During four years of war, Marie’s petites Curies treated an astonishing one million wounded soldiers. Did she do it for money or the fame? Hardly. Despite the great achievement of her petites Curies, despite having offered to melt down her gold Nobel Prize medals which, she said, “are quite useless to me,” the sexist French government never formally recognized her astonishing humanitarian achievements.

Let’s all of us — women and men, in the nuclear industry and outside of it — be like Marie at once. Caring and courageous, fighting for nuclear’s transcendent moral purpose of achieving peace, prosperity, and environmental protection. As Marie said, “Nothing in life is to be feared, only understood. Now is the time to understand more so that we might fear less.”

Thank you.